Intensive is the right name for it

Profiles of four students in the 2013 Uriel Weinreich Summer Program in Yiddish Language, Literature and Culture

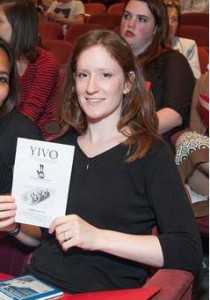

Photo by Melanie Einzig.

I have a master’s degree in Anthropology and Culture, and my M.A. thesis was on the life and legacy of Janusz Korczak [Polish-Jewish educator and children’s book writer who perished in Treblinka with children from his orphanage]. He didn’t write in Yiddish, but in Polish, even though he understood Yiddish very well. But some of his works were translated into Yiddish and, in fact, today, they exist only in Yiddish. I would like to bring them back to Polish, to the language in which they were originally written. That is what motivated me to come here to study Yiddish.

Moreover, I’m also involved in the activities of the Center for Jewish Culture in Warsaw. I lead workshops for them. There is a series of lectures concerning a Jewish area in Warsaw called Muranów, and we’re reading literature about this area and the past, so it’s also very valuable to have these Yiddish insights to the literature.

My primary work is at the Institute of Culture at the Center for Documentation and Research, a branch of the Historical Museum of Warsaw. So I think that having a Yiddish-speaker or at least a Yiddish reader at the museum of a city that was one-third Jewish before the Second World War would be a very good thing. There is no one there who reads Yiddish or Hebrew. But we have Yiddish and Hebrew documents in our archives.

I never realized that Yiddish literature was so rich. In Khane Gonshor’s [Anna Fishman Gonshor’s] class, we had many lovely readings. They were so sad, some of them because the reality was very sad. But at the same time, I’ve learned a lot.

Agnieszka is the recipient of the Shekhter Foundation Scholarship, which provided full support for tuition, travel and living expenses for this year’s Summer Program.

Photo by Melanie Einzig.

There was always a little bit of Yiddish in my life. Not from my family, we’re not Jewish, but I grew up in St. Louis Park, Minnesota, where there was a large Jewish population and many different variations of Jewishness. I had my share of friends who were Jewish and I went to a lot of bat and bar mitzvahs.

So Yiddish was always there in my mind. I never really heard anyone speak it but I knew it was there. And I studied German, and German, of course, is very close to Yiddish, especially Middle High German. And I love the language component of it but I’m also a doctoral candidate in German Studies at the University of Minnesota, and I’m interested in German Jewish literature and concepts of language in translation and to what extent translation can bring in an idea of the sacred. And Yiddish is essential for German Jewish studies.

I find it fascinating that Yiddish is an amalgam of all these different languages, and that you can say one thing with so many choices of words. And that’s how translation can be so difficult, because the words you have in Yiddish carry a choice of where they came from and what language they’re close to.

The teachers in this program are so invested in what they’re doing. And intensive is really the right name for it. It’s been exhausting and wonderful and amazing.

Adelia received a Foreign Language Area Studies Grant from the Department of German, Scandinavian and Dutch at the University of Minnesota, to study in this year’s summer program.

Photo by Melanie Einzig.

I’m interested in endangered languages that are threatened with dying out in the next few generations. That’s the field that I plan on working in, in the future. I just came back from a year-long Fulbright grant in Turkey where I was teaching English and learning Turkish, as well as a bit about the language communities in Turkey. There are Aramaic-speakers who still live in the southeast and Aramaic is a particular interest of mine. And so, interacting with them really brought home how important it is to preserve these languages. Yiddish is something that I had in my heritage and it just feels right that when I’m also trying to encourage other people to preserve their heritage, that I should also be involved in a language that I have in my family and which is threatened.

Right now, my biggest interest is in neo-Aramaic, as it’s called. And Aramaic was a language that was spoken in the Middle East for a long time until the fall of the Sasanian Empire, and it’s survived in pockets among Christians and Jews, throughout northern Iraq (Iraqi Kurdistan), as well as southeastern Turkey and parts of Iran. But I’m also interested in a variety of other languages, including various Jewish languages, like Bukhari and Ladino.

The situation re Aramaic-speakers vs. Yiddish-speakers is very different. On the one hand, you could say that Yiddish is not very endangered at all, because there is a vibrant, Yiddish-speaking community among Haredi [Orthodox] Jews, but outside the Haredi world, I think, you could call it threatened. It’s a very interesting experience to be inside of a movement that’s trying to keep this language alive vs. being on the outside and reading about it. Being inside, you get to experience a lot of the difficulties people face, like inability to use the language on a daily basis or a limited amount of media that you can use. So, for instance, you can’t just get up in the morning and turn on the TV and watch the news in Yiddish.

It’s important to have a really hands-on approach to dealing with the issue of language death.

I think being in this program has given me good insights as to how this can be structured. Yiddish is very interesting because there’s such a strong backing for its preservation that really a lot of other languages don’t have. Other Jewish languages, such as Ladino, lack the base of support that Yiddish has. That’s partly a demographic thing because there really isn’t a large, established community in the U.S. of Sephardim, even though they’ve been here longer than Ashkenazi Jews. I think the Uriel Weinreich Summer Program is a really good example that can be taken and applied to other languages.

Eric is the recipient of the Lili Perski Award, which granted him a tuition waiver for this year’s summer program.

Photo by Piotr Dudek.

I grew up in Ukraine, in Dniepropetrovsk, but right now I’m studying at Kiev University.

I’m studying the history of Eastern Europe and the history of the Soviet Union. As an undergraduate I studied the history of the cinema under Stalin, and right now I am preparing to write about cinema in eastern Poland at the beginning of the Second World War until Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. This area was part of Poland and then it became part of the Soviet Union. There was a particular type of political cinema that was shown in theaters, and it’s really interesting how people reacted to it – what they saw, what they didn’t see, and what they regarded as normal. And I hope to use some Yiddish handwritten materials in my future work, such as the letters of theater and cinema critics, as well as reviews in the Yiddish press.

When my grandmother moved to our house, I asked her questions about her family and she told me that in the time of Stalin, during the Great Terror, her parents sometimes spoke in an unfamiliar language. [Yiddish was used as a secret language.] She also told me that her grandmother was a Jewish revolutionary who was exiled to Siberia in the time of Nicholas II. I found this very interesting and I realized that some expressions she used – bekitser [in short], mayne tsures drey shoyn kop [my head is spinning from troubles already] – were not German.

So these are some of the reasons, professional and personal, that I got interested in Yiddish. Maybe it’s a longing for lost generations: my grandmother didn’t speak Yiddish but her parents spoke it. Also, I likeYiddish revolutionary songs. I’m really interested in the Bund and in the American Anarchist movement. I’ve read everything that Emma Goldman ever wrote.

I’m a member of the Independent Students Union in Ukraine and when I go back home, I’m going to publish an edition of our newspaper in Yiddish, with the best articles from all previous editions translated into Yiddish. And maybe progressive students in Ukraine will realize that Yiddish is a part of Ukrainian history and that it’s not a distant history. And on the other hand, it will provide people who are already interested in Yiddish with Yiddish reading material about modern, contemporary issues.

Yakiv is the recipient of the Lyvia Schaefer/Ester Kodor Cohen Award, which provided full support for tuition, travel and living expenses for this year’s Summer Program.