New York’s Yiddish Theater: Interview with Edna Nahshon

On March 9, 2016, the Museum of the City of New York will open the doors on a new exhibition, New York's Yiddish Theater: From the Bowery to Broadway. A co-presentation of the Museum and YIVO, the Yiddish Book Center, and the National Yiddish Theater-Folksbiene, the show is devoted to the full sweep of the history of Yiddish theater in New York. Artifacts, posters, photographs and more tell the story of how Yiddish theater flourished in New York in the 19th-early 20th centuries to an extent that it didn’t and couldn’t elsewhere in the world, including its birthplace in Eastern Europe.

The exhibition is accompanied by a lavish catalog by curator Edna Nahshon, the esteemed historian of Jewish and Yiddish theater. Nahshon is professor of Theater and Drama at The Jewish Theological Seminary. Her specialty is the intersection of Jewishness, theater, and performance. She is the editor and author of numerous books and articles on theater, including Jews and Theater in an Intercultural Context (2012) and From the Ghetto to the Melting Pot: Israel Zangwill’s Jewish Plays (2005). Her forthcoming book is titled Countering Shylock: Jewish Responses to The Merchant of Venice (Cambridge University Press, 2016).

She spoke with Roberta Newman on March 2, 2016 about the exhibition and her research at YIVO.

RN: What makes Yiddish theater a particularly intriguing topic, do you think? Why do you recommend that people flock to the exhibition?

EN: Yiddish theater is part of our history. It's part of our identity. In fact, for many people it's more longevity in terms of its visibility than the Yiddish books and even the Yiddish newspapers because there was a whole generation that is still around that grew up with Yiddish that cannot really read a book in Yiddish but can relate to a show. It's very much alive in memory.

I myself remember seeing Molly Picon. There are still many people for whom “Yiddish theater” is not an obscure term. There's also a body of Yiddish film that preserved much of it. It's part of the heritage of Jews in general, and of American Jews in particular, because New York was the capital of the Yiddish theater. And it's also very much a part of the New York theatrical scene, and by extension, the American theatrical tradition.

There's something very nice that the grandson of Stella Adler, who's the great-grandson of Jacob P. Adler and Sarah Adler, said. (He's still running the Stella Adler Studio.) He said, "You have to know where you're coming from in order to know where you're going." This is where we're coming from. Clearly, we don't have and I don't foresee that we shall ever have the kind of vibrant Yiddish scene that we had from the turn of the last century until shortly after World War II--but this where we come from. We are our memories. I mean, why have YIVO? It’s for the very same reason. It nourishes us. It also ignites the imagination, not only of scholars but also of artists. Paula Vogel, the Pulitzer Prize winning playwright, has a new play out, Indecent, that deals with the controversy over Shalom Asch’s 1923 play God of Vengeance, a Yiddish play that was translated into English for Broadway.

RN: It was really in New York that Yiddish theater had its first heyday, correct?

EN: The only heyday it ever really had! Because as important as what you had in Russia, in Poland and in a couple of other places, New York is where the money was. New York was where the audiences were, in the millions. New York had freedom. You did not have to accommodate all kinds of political yea- and naysayers. Not here.

RN: And that heyday was around the turn of the century?

EN: The first Yiddish production in New York takes place in 1882. This is barely six years after Abraham Goldfaden had his first Yiddish production in Romania. Yiddish theater in America starts with the mass migration to the United States. Nearly all the actors from Eastern Europe, (sometimes via London) end up in New York but there's an additional issue because in tsarist Russia there are restrictions on Yiddish theater. But the writers and actors flock here because the audiences and the money are here.

Yiddish theater in New York develops very rapidly. The first theater built specifically for Yiddish theater, not just a temporary performance space, so to speak, is built in 1903. That's the Grand Street Theater. It's a huge theater. It's a very elegant one. The mayor and all kind of important people in New York come to the opening because at that time, I don't know how comfortable they would have been going to a synagogue. You went to the theater to see Jews, talk to Jews and celebrate this whole new Jewish life in New York.

RN: And this vibrant Yiddish theater scene lasted until World War II?

EN: It all does extremely well until the end of the mass Jewish immigration. That was the constant feeder, of course. Then we start to have a slow process of decline, which truly becomes very fast after the second World War. It's not the end of the Yiddish theater--by no means--but at that point, it becomes something for older people only, an ethnic enclave kind of theater. The younger generation goes to Broadway. The major playwrights stop writing so much for the Yiddish stage.

RN: How do you come by your interest in Yiddish theater?

EN: That's a good question. I grew up with a stepfather who was a Yiddish journalist. That's how he made his living in Israel. He worked for Letste Nayes. This whole Yiddish milieu—Dzigan and Schumacher and Ida Kaminska, Maurice Schwartz, etc.—was very much part of the ambiance in which I grew up. I studied theater. Then when I came to NYU and got my advanced degree, I thought of doing something on Yiddish theater.

The first time I went to do research on Yiddish theater, YIVO was still located on 86th Street. That was a first visit that could make me or break me! I had a fabulous reception. I came in. I was literally hugged. It felt like I was coming home. People were extremely nice to me. Of course, they started arguing with me. The first question was, "Where did your family come from?" They started arguing and correcting me (even though I was right and they were wrong!) but it didn't matter. Right away, it was "Meydele [young lady], do you want coffee? Do you want tea?"

Marek Web [YIVO’s Chief Archivist at the time, now Senior Research Scholar] was there. He was really wonderful to me. It was natural. I settled down in New York. I started working. I wrote my dissertation. My book on ARTEF, a Communist-affiliated theater that was very interesting in terms of its art, came out. That was the beginning of my long engagement with the material.

RN: How did the exhibition at the Museum of the City of New York come about?

EN: The project started with something a little abstract: the connection between Yiddish theater and its impact on American theater. I pushed it more towards Yiddish theater, though it was very clear that the American theater would also be part of the exhibition, and that it would be a journey, taking us from the earliest days of the Yiddish theater to today. It's very easy to say, "Yiddish theater had an influence on American culture,” but when you try to prove it, it's not so simple. The fact that the parents of this or that actor were Yiddish-speaking immigrants does not prove that the Yiddish theater influenced the American theater. That is very often the argument. Look at Paul Muni. He was a Yiddish actor. Then he became this big star in Hollywood and on Broadway.

I was really looking for a better link. And I found it in the Catskills. It was a Jewish space: keeping kosher or fasting or going to shul in the morning and to the pool afterwards was natural, was part of the scene. What you had there is the whole culture of the Yinglish with a Y, this mish-mosh of English and Yiddish, which is confined for a while to the Catskills and then becomes part of American culture. As the Catskills die, American culture absorbs much of it. This is where I see the connection and the influence.

Then, of course, there's the personal influence, the fact that there were people who were the children of the Yiddish theater. The Adler family's just a great example of that. In fact, it's one of the great dynasties of the American theater. Jacob Adler, olev hasholem [may he rest in peace], had a lot of kids. I think he had nine or ten. All of them ended up in the theater.

RN: You did a lot of research at YIVO for this show, and, in fact, YIVO is the lender of many artifacts that are now on display in the exhibition.

EN: YIVO was my treasure house, I have to say. I came here with my assistant, Stephanie Halpern, who was really my right-hand and should get all the kudos in the world. She's wonderful and terrific. We found really wonderful things. For instance, we were looking for material on Yiddish vaudeville, because hardly anything has survived from this genre. It wasn’t preserved because it wasn’t considered sufficiently literary. So how do you show it?

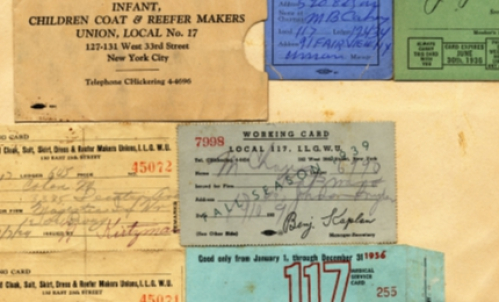

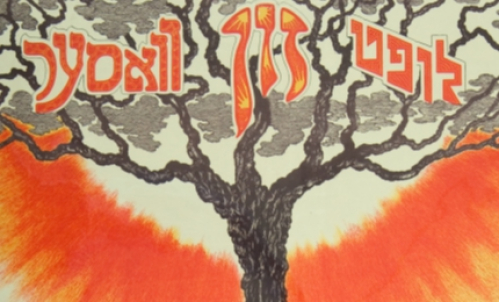

Then we stumbled over materials that belonged to a vaudeville star, Mae Simon. We had shoes. We had makeup. We had feathers. We had the costume. It suddenly gives the whole thing life. Another terrific thing we found is the banner of the Hebrew Actors Union. It's one thing to talk about the unionization of the Yiddish theater. It's another thing to show a banner, the original banner, from 1900, in Yiddish.

Really I also have to say that for me, YIVO is home. I care a great deal about it. I'm looking forward to many more years of research and collaboration.