Six Maskilim Integral to the Jewish Enlightenment

European legal reform in the 18th and 19th centuries enabled new possibilities surrounding the greater integration of Jews into secular society. The Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment, was a social movement that emerged in the wake of these reforms, advocating for the integration of secular studies into Jewish thought while maintaining Jewish society as a distinct entity. The adherents of Haskalah were known as maskilim, and they played an essential role in cultural renewal and the foundation of modern Jewish political movements.

|

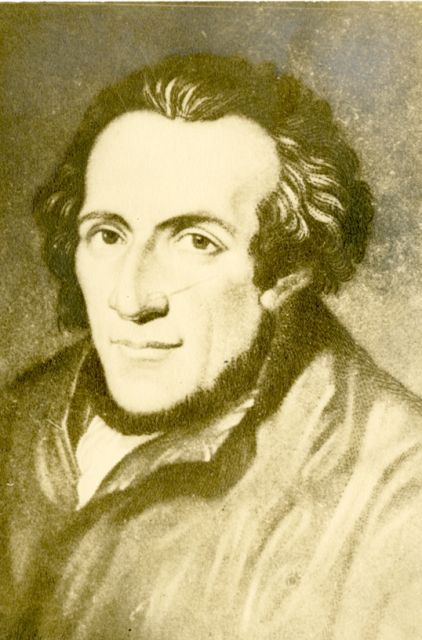

Moses Mendelssohn (1729-1786)Mendelssohns’s writings and formulations were foundational in the early stages of the Haskalah movement and paved the way for other maskilim. Committed to both secular studies and Jewish tradition, Mendelssohn embodied the quintessential fulfillment of the Haskalah’s ideals and social ambitions. An illustration of his dual identity was his argument that Judaism had no tenets of faith that could not be arrived at through human reason. |

|

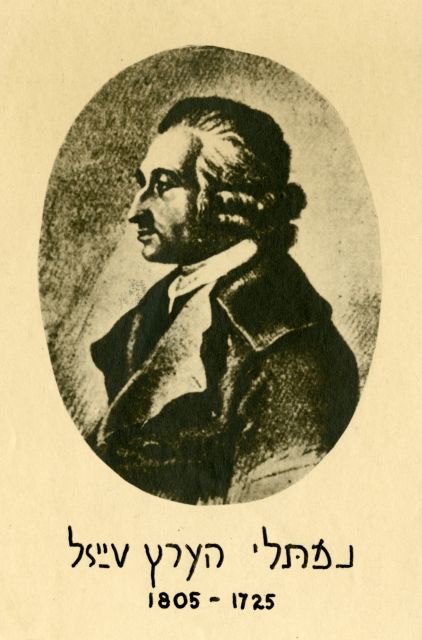

Naftali Herts Wessely (1725-1805)Wessely published Divre Shalom ve-Emet (Words of Peace and Truth), where he distinguished between divine revelation or the “Torah of God” and secular studies, which he called the “Torah of Man.” Wessely saw Hapsburg Emperor Joseph II’s 1782 Edict of Tolerance, which granted new civic rights to Jews, as an opportunity for Jews to gain a secular education and finally be able to begin developing the Torah of Man. |

|

Yosef Perl (1773-1839)Despite being a former Hasid, Perl, a prominent educator, became one of the most ardent authors of anti-Hasidic literature. Between 1814 and 1816, he composed his first diatribe called Über das Wesn der sekte Chassidim (On the Essence of the Hasidic Sect) in which he accused Hasidim of responsibility for the cultural backwardedness of the Jews. In the end, Perl found little success in his anti-Hasidic endeavors, but the antipathy of maskilim towards Hasidism remained a defining characteristic of the Haskalah. Learn more: YIVO Encyclopedia |

|

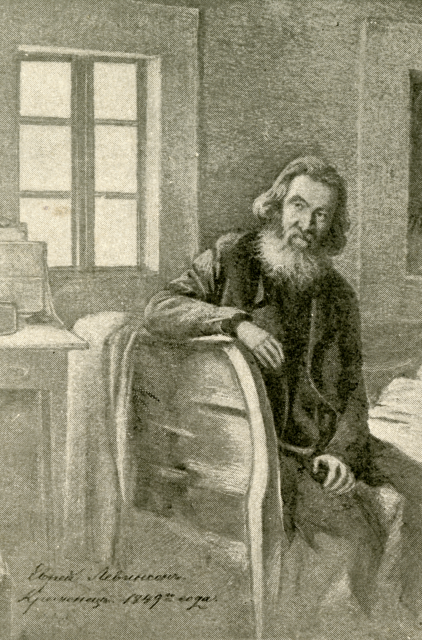

Yitshak Ber Levinzon (1788-1860)Levinzon’s primary contributions to the Haskalah were his writings; the most widely circulated being Te‘udah be-Yisra’el (A Warning to Israel). In the book, he used religious texts to promote greater integration of Jews into the secular work and studies of Eastern European society. Like Perl, he is famous for his antipathy towards Hasidism. While Levinzon made considerable contributions to Haskalah, his poor health and lack of finances were constant impediments throughout his life. Learn more: YIVO Encyclopedia |

|

Max Lilienthal (1815-1882)A scholar and rabbi from Germany, Lilienthal is best known for his efforts at educational reforms in the Russian Empire. The Russian Education Minister, Serge Uvarov, enlisted him to assist in reforms that aimed to expose Jews to secular education. Ultimately, the reforms were met with little success; nonetheless, the involvement of government agencies in Jewish cultural affairs marked a strong deviation from the norm for the Russian Jewish community. Learn more: YIVO Encyclopedia |

|

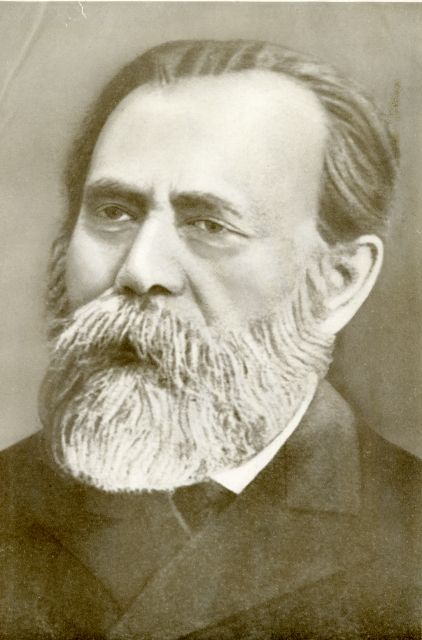

Leon (Lev) Pinsker (1821-1891)Pinsker is best known for his German-language brochure Autoemancipation: Mahnruf an seine Stammesgenossen von eimem russischen Juden (Autoemancipation: A Call to His Brethren from a Russian Jew). Increasingly disillusioned by pogroms and anti-Jewish sentiment, he posited that anti-Semitism was an incurable disease that fluctuated in relation to economic and social circumstances, and argued for the establishment of a Jewish homeland. Although he did not believe that the homeland should necessarily be established in Palestine, the Zionist movement came to view Pinsker as one of its ideological fathers. Learn more: YIVO Encyclopedia |

These profiles of six maskilim paint a brief characterization of the larger Haskalah movement. Although some of the outcomes of their ideology were far from their architects’ intentions, the movement was fundamental for the foundation of secular Jewish culture and the rise of modern Jewish political movements.

For a more in-depth history and suggested readings, please visit the YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe.