Caring for and Learning the History of a Book Published in 1694

by J.D. ARDEN, Reference and Genealogy Assistant, Center for Jewish History

Last week, April 27 – May 3, library and archival institutions observed Preservation Week. Among them, the organization Heritage Health has been working for the past decade on raising awareness of the state of cultural heritage collections in the U.S. In Fall 2014, they will launch a survey of sites and collections, the Heritage Health Index.

Here at YIVO last week, one book that I helped the Archives Conservator to clean and prepare for long-term preservation and digitization was the Sefer Beit Shmuel, a leather-bound but extremely dilapidated tome, about 1 foot in length, that is amazingly legible despite years of dirt and damage. In the course of carefully brushing away dirt and smoothing down its creased pages, I was intrigued to learn more about the history of this book. Talking to YIVO’s Head Librarian Lyudmila Sholokhova, and Project Archivist Shmuel Klein and looking around the archives, this is what I learned:

The story begins in the town of Dyhernfurth near Breslau (present-day Wroclaw), in the Austro-Hungarian Empire of that time. A 47-year-old man named Shabbethai ben Joseph Bass, born in Kalisz in central Poland in 1641, had finally received official permission in 1688, after almost four years of negotiations with bureaucrats, to open the first Hebrew-language printing press in the region. Until then, Prague and Amsterdam were the closest available centers of Jewish publication. He had to assemble his own Hebrew book-making staff from scratch because there had been no Jews in the Province of Silesia since an official expulsion in 1584.

The very first book to be printed on the presses of Mr. Bass had been written by a rabbi from the Polish town of Wodzislaw – Rabbi Samuel ben Uri Shraga Faivish. The book was a compilation of commentaries on the fourth section (“Even Ha’ezer” – The Stone of Help) of the Shulchan Aruch, a compendium of Jewish legal discussion relating to aspects of daily life written by Joseph ben Ephraim Karo in Safed, Ottoman Palestine in 1563. Section Four deals with marriage, divorce and sexual conduct.

But this is not the Sefer Beit Shmuel that is being preserved here. In 1691, Rabbi Shraga Faivish was appointed to Fürth, Germany, and three years later, he found another Hebrew publisher there to print a second edition of his book with additional commentary he had been working on. That is the 1694 edition, one of only four in the world (all in the United States), that I cleaned the dirt and mold off of with a sponge-eraser this week, under the helpful eye of Library and Archives Conservator, Tatiana Popova.

So what happened to this book since it was published 320 years ago?

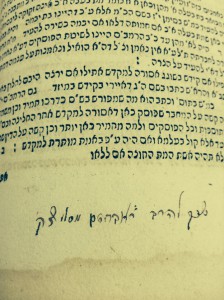

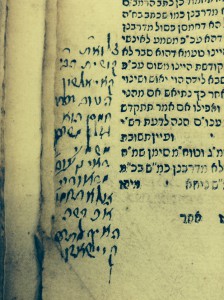

The only clues the handwritten margin notes and the book stamps found among the pages. There are only a few points (so far) that identify either an individual or a place in the Sefer Beit Shmuel’s life line:

- Some of the marginalia mention a Rabbi Avraham of Slutsk – a town in present-day Belarus. A probable match of that historical figure is found in the Slutsk Yizkor Book, here. This puts the book in his hands, in the region of Belarus, in the nineteenth century. It is likely that it was from this Slutsk family lineage that the Sefer Beit Shmuel eventually was incorporated into the collection of the Strashun family or their library in Vilna.

- There is also a note and illegibly messy signature in Russian, claiming that the book has been approved by the censorship of the “official rabbi” of whatever municipality of the Russian Empire it was in at the time. (Read more on the role of the “kazyonny ravvin”.)

- The earliest book stamp found was that of Mattityahu Strashun Vilna Community Library. Born in 1817, the son of a Talmudic scholar in Vilna, Mattityahu Strashun was a rabbi, scholar and collector who amassed a personal library of some six thousand books that he bequeathed to the Jewish community of Vilna (present-day Vilnius) after his death in 1885. This library opened to the public in 1893. It was therefore, sometime in or after those years of the public Strashun library that the Sefer Beit Shmuel was acquired (one of more than 33,000 books in the collection by 1931).

In 1941 the Strashun Collection was looted by the Nazis. Some books were destroyed, but many were taken to the German city of Offenbach. Ironically, a number of books and artifacts were stored by the Nazis during the War with the intention of eventually creating a “museum of the extinct Jewish race,” to be housed in what had been the Prague Jewish Museum. Whether or not the Sefer Beit Shmuel was part of that intended plan—this book survived.

After the war, in 1947, the books of the Strashun Collection were integrated (in some cases re-integrated) into YIVO’s collections, some of which had also survived, in horribly precarious storage conditions. And this is where the Sefer Beit Shmuel of 1694 will remain, being cared for, restored and eventually digitized, to be available to generations of scholars to come. I am glad to have played a small part in that process.