Modernism, Gender, and War in Early 20th Century Hebrew: Interview with Beverly Bailis

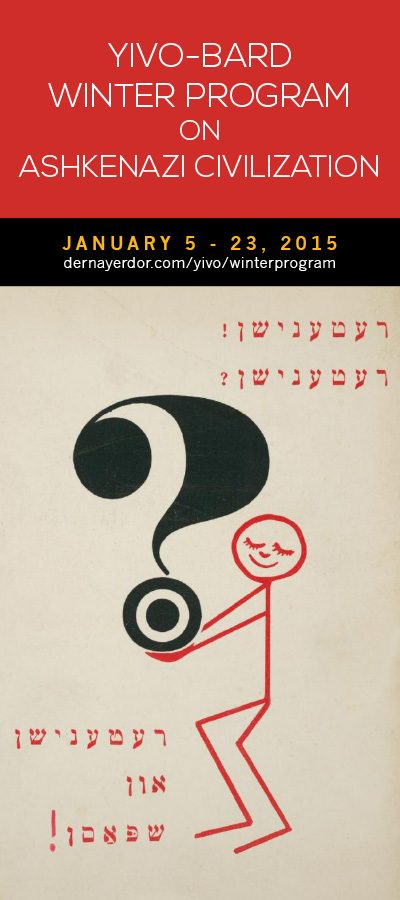

From January 5-January 23, Beverly Bailis will teach “Modernism, Gender, and War in Early 20th Century Hebrew” in the YIVO-Bard Winter Program on Ashkenazi Civilization.

She currently teaches Hebrew and Hebrew literature at Brooklyn College. She received her BA in Literature from Bard College, her M.A. in Jewish Civilization from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and her Ph.D. in Hebrew Literature from the Jewish Theological Seminary. In addition to specializing in Modern Hebrew Literature, Bailis’s research interests include Modern Jewish Literature, Gender Studies, and Modernism. Recently she completed her dissertation, “Fantasies of Modernity: Representations of the Jewish Female Body in Turn-of-the-Century Hebrew Fiction.” She has taught courses at the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS), the Women’s League for Conservative Judaism, the JCC in Manhattan, Town and Village Synagogue, and other adult education programs in New York City.

She is interviewed here by Leah Falk.

LF: Your course will examine Hebrew texts set in Europe in the early 20th century—departing, as you say, from the idea that Hebrew letters at the time were inextricable from the Zionist narrative. For Hebrew authors who wrote about European subjects, what was the motivation for writing in Hebrew, rather than in Yiddish or the language of each author’s native state? To what extent was the choice to do so—as in the case of Lea Goldberg—connected to Zionism? To what extent was it consciously separate?

BB: The idea for this course arose in part from what I see as an exciting moment in the study of Hebrew literature, due to recent scholarship that looks at early 20th-century Hebrew literature that was written in or about Europe within a European context, as opposed to an exclusively national or Zionist framework. In fact, I believe that the recent attention to the European context of early 20th-century Hebrew literature is part of the reason why a course specifically on Hebrew literature is relevant to a Bard-YIVO Winter Program that focuses on “Ashkenazi civilization.” In this context, the marking of the 100th anniversary of World War I affords an excellent opportunity to revisit early 20th-century European war literature written in Hebrew through a new lens that places these texts in their specific European locations, which range from Budapest, Berlin, and Kovno [Kaunas], to Odessa, and within the framework of transnational literary responses to war.

You are absolutely right, though, that the choice for Jewish writers to write in Hebrew is significant, both for how the authors represented the war, and how the works resonated within an emerging national context. However, while the choice of Hebrew as a language for Jewish writers may have been tied to a certain extent with the Jewish national project, the lives and backgrounds of Hebrew writers of this period were likewise inextricably interwoven with the European experience, and their writings were part of the European intellectual environment in which they were written.

An interesting example, as you suggest, is Lea Goldberg’s work. Her novel that we will read in the course, And This is the Light, which was published in 1946 and set in Kovno in the beginning of the 1930’s, has not to my knowledge been read as a “Great War novel.” In fact, when it was published it was largely dismissed by Hebrew critics as “too personal,” autobiographical, and not of larger interest (at a time when Hebrew literature was expected to take on “collective” concerns and be bound up with nation-building). Such early evaluations of the novel, I believe, have eclipsed one of the novel’s central aspects, namely its preoccupation with memories of wartime and the legacy of the Great War. The novel explores the impact of the war, both on larger historical processes and on the individual consciousness and psyche. While Goldberg’s work, in general, is a part of Israel’s canonical national literature, and parts of the novel depict the main female protagonist’s decision to become a Hebrew writer and move to Palestine, there is a kind of tension between “national concerns” and what you refer to as general European subject matter. The way the novel focuses attention on a “non-Jewish” war that affected all of Europe, and brings to the reader powerful visceral images of the horrors of war, clashed with the general ethos and needs of the readership in the Yishuv in Palestine at that time, which was in the throes of recovering from WWII, and on the verge of the War of Independence. This may also have contributed to the novel’s shaky status in the Hebrew canon. Only recently has this novel begun to be reevaluated by literary and feminist critics, who have pointed to the various important social and political aspects of this fascinating novel.

LF: At the point when the novels and poems you’ll explore were written—roughly between 1919 and 1952—there was still a relatively small circle of Hebrew belletrists. How do you think the size of the readership that had access to these works made a difference in their critical reception? How do you think Hebrew readers, especially Israelis, read these works differently now?

BB: Interestingly, the relative newness of the Yishuv in Palestine and then Israel, as well as the relatively small Hebrew readership at this time, were actually propitious for one of the key texts we will be reading in the class, the Hungarian writer Avigdor Hameiri’s The Great Madness. Published in 1929, it is considered the first Hebrew “bestseller” in the Yishuv. This novel chronicles Hameiri’s experience in the Austo-Hungarian army in World War I, and reads as an adventure or detective story. It is driven by action and plot and is written in a robust, fast-paced Hebrew. On one hand, the novel filled an important void in Hebrew literature at that time, which had very little popular fiction that could be enjoyed by all parts of the emerging Hebrew readership. It also provided readers with a sense of pride. As Avner Holtzman has illustrated, Hameiri was considered a kind of “Hebrew Remarque.” Both The Great Madness and All Quiet on the Western Front appeared in the same year, and both works may be read as “pacifist” novels. At the same time, the novel certainly spoke to a “Zionist” audience; it focused on the “Jewish experience” of the war, and featured many images of heroic Jewish soldiers, as well as key moments in Zionist history that occurred during the war, such as the signing of the Balfour Declaration. The Great Madness is still considered Hameiri’s most important work, and while it was probably not in the forefront of most Israelis’ minds in recent times, the 100th anniversary of the war, and the novel’s unique status as representing the experience of Jewish soldiers in the Austro-Hungarian army, should make this novel highly visible again.

Aside from Hameiri, the other authors we will read in the course are all central, canonical figures, such as Goldberg, Agnon, Tchernichovsky, Brenner, and U. Z. Greenberg, so these works are still very much “on the map” of Hebrew literature. Moreover, a number of these works have also been discussed in Glenda Abramson’s important book, Hebrew Writing of the First World War. And even though the Agnon novel that we will read, Ad Hena, has been considered “fragmented” and its complexity has posed a challenge to many readers, and Goldberg’s novel had originally been dismissed nearly altogether by Hebrew critics, I believe that the recent interest in Hebrew modernism and in women’s writing in general, coupled with renewed interest in the Great War, will render these works highly relevant to contemporary readers. The recent translations of these novels into English (Ad Hena was translated for the first time into English in 2008, and And This Is the Light in 2011) will also make these works more accessible to an international readership.

LF: Your syllabus asks a fascinating question: “Did Hebrew war writing of this period call for new models of thought and expression, or was the language of decline, collapse and fragmentation already in place in Hebrew writing since the turn of the 20th century, due to the many seismic shifts and breaks in traditional life, experienced as a part of the Jewish confrontation with modernity?” If the answer to the second half of this question is yes, you might be suggesting that early 20th-century Hebrew writing foresaw the changes in genre and form that modernism brought to European literature. Do you believe this to be the case?

BB: Some recent scholarship has made this case, such as Shachar Pinsker’s book Literary Passports: The Making of Modernist Hebrew Fiction in Europe. There, he writes that Hebrew writers at the beginning of the 20th century “…did not have to ‘wait’ for shocks like the Great War or the Bolshevik revolution. The experience of shock and unsettling upheaval was clearly felt at the turn of the twentieth century, and with very distinctive purchase by European Jews. This provides another explanation for the deep and rapid modernist change that erupted in Hebrew fiction on or around 1900.” So following these lines, if one looks at much turn-of-the-20th century Hebrew literature in terms of its narrative fragmentation, focus on subjectivity, interest in urban experience, etc., such works may very well be viewed as early examples of what came to the fore in later modernist literature that appeared throughout Europe.

The literary works under discussion here are of course from a little later, beginning in 1919, a period already clearly identified with modernism in Europe. While some of the authors on my syllabus have been considered “modernist” writers, and others have been seen as turning to more “traditional” forms of representation, what I am particularly interested in asking in this course is how these Hebrew texts represented this period of total war. I hope to explore with students what these texts can add to the transnational literary responses to World War I and its aftermath by adding the specific case of Hebrew, as well as how the lens of European modernism can help us see new aspects of these war-related texts, and their ethical, social, and political implications for our own historical moment.

Register for "Modernism, Gender, and War in Early 20th Century Hebrew Literature"

Leah Falk is YIVO’s Programs Coordinator.