Not to Let Them Sink Into Anonymity: Interview with Isabelle Rozenbaumas

Somewhere around 2008, the French/Brooklynite historian, filmmaker and translator Isabelle Rozenbaumas launched a project, Bat Kama At? (How old are you?), a historical, art, and educational project about the lives and fate of 500 girls from the Yavne Girls’ Gymnasium in Telsiai (known in Yiddish as Telz), Lithuania, where her mother was a student before World War II. The girls who remained in Telz during the Nazi occupation were massacred in December 1941.

Rozenbaumas’ project is multi-faceted. She has gathered documents, testimonies, and photographs from all over the world, seeking to identify as many of the girls and women from the Yavne school in Telz as possible. She has also worked with the Telsiu Vincento Boriseviciaus Gimnazija School, a Catholic high school in Telsiai, on a project in which students study interwar Jewish life and education in Lithuania. One of the ultimate goals of Bat Kama At? is an installation of 500 portraits of the Yavne students in the open air in Telz, that will be designed to later travel to other venues.

Read more about Bat Kama At? at its website and in this blogpost by Rokhl Kafrissen at Rootless Cosmopolitan.

Rozenbaumas is the recipient of a 2013-2014 Baltic Jewish Studies Fellowship from YIVO’s Max Weinreich Center. She was interviewed by Yedies Editor Roberta Newman.

RN: What was the inspiration behind your project?

IR: The story began in 2000 when I was making a documentary film in Lithuania about the vitality of Yiddish culture in Lithuania, in the place where I was born. I was born in Vilna of Telzer parents, parents from Telz. But this isn’t a project about genealogical research.

Near the end of my time in Lithuania, I went to my parents’ shtetl, where I had briefly been earlier to check out locations for the film. So there I met the last survivor, the “president” of the three remaining Jews in Telz. That was almost fifteen years ago; today, there is no one left. And one of the places he took me and my co-filmmaker Michel Grosman was the place of massacre of 500 girls of the city of Telz. Their fathers were shot two weeks after the Germans arrived in Telz in July 1941, and their mothers and brothers and sisters in September. The girls were kept in a ghetto, forced to work and probably used as sexual slaves. (I haven’t done an investigation of that aspect of the story. For many reasons, I can't talk about that today.) The girls were shot at Christmas time in 1941, six months after the assault of the Germans.

When I came back home to Paris, I was paralyzed. Somehow, I couldn’t think of anything else but their fate. I owed them something. So I wrote “Les Jeunes Filles et la Centrale Nucleaire,” which you can read in French on my website. It was in 2001, just at the point when Lithuania was a candidate to join the EU [European Union] and I sent this letter to many people responsible for European relations, such as officials and Madame Simone Veil [who served as Minister of Health under Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, President of the European Parliament, was a member of the Constitutional Council of France and was recently appointed President of the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah ]. And Madame Simone Weil answered me, "Why don't you present your film?" I had mentioned my documentary film but that wasn’t the point I wanted to make. What I was writing about was the fact that Lithuania was going to be given billions to dismantle a Chernobyl-like nuclear plant, but in the meantime, it had dirty hands when it came to the memory of its Jews. And that’s why I called the text “The Girls and the Nuclear Power Plant.”

So we completed our film and we were fortunate to receive support from the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah. In the meantime, I was thinking of those young girls and I asked my mother to show me the three class pictures that I remembered from my childhood. And seeing those three class pictures, I understood that some of the 500 girls were in them. But it took me a few years—during which time I completed the film and produced an English version—to decide to put a name on each face. Not to let these girls sink into the night of anonymity.

RN: What did you find out about the girls as you began to do research?

IR: I had a sort of personal relationship with them through the stories of my mother. Not that she remembered each girl—but she did remember a few girls. She remembered each teacher and she had very interesting stories about the secondary school, the Yavne Gymnasium [high school] where the pictures were taken, that intrigued me very much. Because the students took Latin, for instance. You notice, in one of the pictures, that there is a skeleton that shows the physiology of the human body, as well as a map of the world. And she could name her natural sciences teacher. I knew that she had been educated in a very religious school and further research has shown that the school was under the influence of the rabbinate of Telz. And at some point, these rabbis decided to give a very high level of education to their daughters and the daughters of the city. The photographs reveal the negotiation between religion and modern education.

Intellectually and by training, I'm a historian. I am as much the daughter of Max Weinreich and Pierre Vidal-Naquet as I am of my own father, who was a scout in the Red Army. So I began to conceive of this project as having the very strong historiographical approach that I was taught by my teachers.

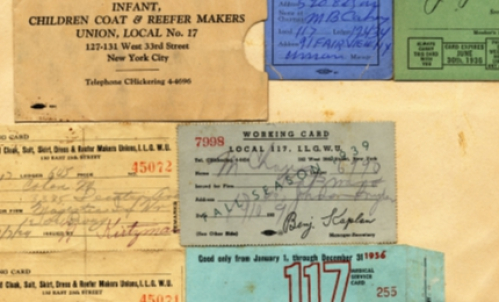

First of all, it's not the history of the Shoah that I set out to research. There is a history behind it that is unknown: the history of the lives and education of these girls. I very quickly made that distinction. And then, I had an intuition that I would be able to find archival material. In 2008, I began to travel to Israel and Lithuania to interview the last survivors in order to fill in the names of the girls. And from the survivors, I collected new photographs. Then, around 2010, I was in Washington, where my husband had a job. So I did a lot of research in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and I discovered a file of about 900 names from Telsiai.

So the project had two steps. First, I began with doing IDs, compiling a photographic archives with the names that I was fitting to the faces. I came up with the idea of placing 500 banners in the marketplace of Telz showing photographs and names, but also displaying faces that don’t have names and names that don’t have faces.

But something changed when I found the archives of the school in the Lithuanian Central State Archives in the fall of 2011. I found 486 files. And then suddenly I was faced with something like 350 diplomas, maybe 200 of them with photographs, excellent quality photographs. I have so far been able to put a hundred 100 of these files online.

This photograph from the family archives was saved by the author’s mother through the war. It was not dated. For her safety, Rosa Portnoi cut out the Hebrew inscriptions that were in the top center. In 2008, the author noticed a photo montage in the personal album of Tuvie Balshem, one of the editors of the Sefer Telz, showing 8 class photographs of the Yavne elementary school from 1931, 4 classes of boys on the right, and 4 of girls on the left. The second photo (2nd year of elementary school) of the girls is almost identical to the one of Rosa Portnoi, the little girls are in the same order, the teachers are missing on both sides but their portraits are in the middle of the photo montage. We know now for sure that this photo was taken the same day of 1931. Before having discovered the existence of the Archives in Vilnius, the authorlearned a lot from this photograph and from her mother’s narrative. From the presence of the écorché and the skeleton, the map of the world, the importance of the sciences and of geography was obvious. Both parents of the author have identified the Professor Pshadmeski (top left) who taught gymnastic in the girl’s school as well as in the boy’s heder, Professor Blekhman who has completed her studies in the gymnasium Yavne in 1928 (married Kimhi, middle left) taught humash, and Professor Poretz (bottom left) taught religion. The professor Golub (middle right) taught mathematics and was both feared and beloved by the children.

Professor Abba Manchovski (bottom right) was the director of the elementary school. He was also the uncle of Reyzel Berkman ‘s mother, Dvoyre Manchovski. The name of the young man standing (top right) Yoel Dov Saks, the administrator of the Yeshiva was recently given to the author by the rebbetsin Shoshana Gifter (née Bloch).

RN: Your own mother was in the gymnasium but managed to leave and spend the war someplace other than Telz?

IR: My mother dropped out of high school in probably 1937 after two or three years because she was the eldest of eight and she had to work. And her father was a balegole [wagon driver]. He was the balegole of Telsiai. It was a very poor family. But he managed to escape with the Soviets when, during the onslaught of the Germans, the Soviets retreated in June 1941. He took his whole family in his carriage plus the entire court [neighbors from the same courtyard]. You know how it used to be in the shtetl. Telz was a very small shtetl. There were 7,500 people and among them, maybe 3,000 Jews.

But even so, Telz had either a new school or an enlargement of a school every second year. And so I call it the campus. They had an elementary school for girls and boys; they had a yeshiva with between 250 and 400 guys each year, with a worldwide reputation. They had a training school for teachers where they opened a section for girls after two years. And they created the Yavne school in the 1920s.

RN: There is an educational component to your project. Can you tell us some more about that?

IR: In 2010, I knocked on the door of the Christian high school in Telsiai. I was with Simon Davidovich, who was at one time the president of the Kovno community and later on the director of the Sugihara Museum (in Kaunas). He is a distinguished guide of Jewish places in Lithuania and knows each of the 250 places of mass murder. It wasn’t the first time he was traveling with me as a guide. And he told me, “It’s June 16. Everyone is off. You are not going to find the director. And what you are asking for is absolutely....” I said, "Please, let us try." So we entered, we knocked at the door. There was only one concierge and one secretary in the whole school, aside from the director. No students. And there I was with my scrapbook. It's very important. It's where I put my photos and it’s where I work with my witnesses. There are photos between pages of notes and names. It's very difficult to work with older people, to film them, to take down their stories, the details they describe, dates, and names and phone numbers of surviving friends. Often, they are blind or deaf or have galloping Alzheimer’s. Finally, at the end, I’ve found a methodology that works! But I was able to visit only a few of them more than once. And if you come back a few years later ...

So I had this book with photos and I told the director, this is not only the history of the Jews—it's the history of this place, of the young people who lived here and of those who live here today.

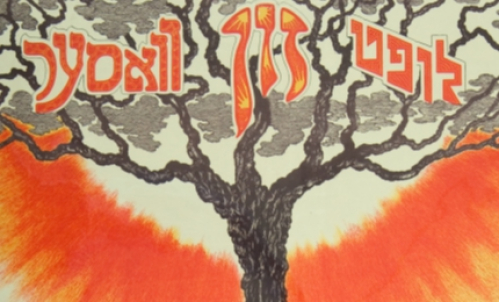

And fifteen days later, he wrote me back that he had accepted me at the school, and so I went back and forth for two years, working with classes. Most of the projects were not finalized before the students went off to university and work, but in the meantime, I had contact with the art academy and with Romualdas Incirauskas and his wife Zita Incirauskiene – two wonderful artists - and they understood my project and came up with an approach where the students learned about this history and then produced artwork in the media they chose. Romualdas had already done a lot of his own artwork about the Jews of Telsiai, and his work is in the Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum.

RN: I was going to ask you to explain the name of your project. Why Bat Kama At?

IR: Bat Kama At comes from a story that my mother used to tell about herself as a student at Yavne Telz. There was schoolwork that she had to do, something that she had to write in Hebrew and she began with "B'nuray" [when I was young]. She was only twelve years old. "B'nuray!" My mother was such a good Hebrew-speaker. Everyone who heard the way she spoke was sure that she had lived all her life in Eretz Yisrael [the Land of Israel], which was not the case. And her Lithuanian was also great. So, “b'nuray,” and the director comes back two days later and he says, "Roza Portnoy, can you stand up?" And he asks her "Bat kama at?" [How old are you?] So that's the story. She repeated this story over and over. And when I discovered the extent of the tragedy of Telsiai and the girls, I thought of this anecdote.

When my mother came back with my father in 1992, she didn't want to go back to Telz. She never went back because she didn't want to meet the ghosts of her friends.

Interview edited for length and clarity.