The Center of Jewish Scholarship – A Portrait of YIVO in 1939

Introduction to the English Translation

My father, Rabbi Noah Golinkin z"l, was born in Zhitomir, Ukraine, on the eighth night of Chanukah, 1913, to Rabbi Mordechai Ya'akov and Chana Chaya Freida Golinkin. When he was about seven years old, his family fled to Vilna in order to escape the Petlyura massacres.

The rest of his life can be divided into four periods.[1] He spent his formative years, ca. 1920-1938, in and around Vilna where he studied at the famous Ramayles Yeshiva together with the Yiddish writer Chaim Grade, as well as in a Polish gymnasium. He also spent time at YIVO, as is evident from this pamphlet. After graduating with a law degree from the Stefan Batory University in Vilna, which was rife with anti-Semitism, he realized that there was no future for the Jews of Poland. In February 1937, he wrote to Yeshiva University in New York and asked to study there; he finally arrived in the U.S. with a student visa in June of 1938.

He spent the years 1938-1941 obtaining visas for his parents and two sisters, thereby saving their lives. In 1942-1943, he, and two classmates at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, spent most of their time trying to save the Jews of Europe. They founded the European Committee and organized dozens of interfaith rallies throughout the United States, especially during the Sefirah season between Pesach and Shavuot 1943. (Dr Rafael Medoff and I told their story in detail in our book The Student Struggle Against the Holocaust, Jerusalem, 2010.)

My father spent the years 1944-1986 as a successful pulpit rabbi; his three main pulpits were in Arlington, Virginia; Knoxville, Tennessee; and Columbia, Maryland. He was also a social activist, for the Civil Rights and Soviet Jewry movements. For example, in 1970, he convinced a group of teenagers in Washington D.C. to undertake a "Fast for Freedom" which became a daily vigil in front of the Soviet Embassy and that lasted until the fall of the Soviet Union.

In 1963, my father developed the Hebrew Literacy Campaign in Arlington, Virginia, which taught adults how to read prayer book Hebrew in twelve lessons. It was adopted by the National Federation of Jewish Men's Clubs in 1978. Together with my mother Devorah Golinkin, z"l, he spent much of his time after 1978 --and all of his time from 1986 until his death in 2003-- teaching adults how to read Hebrew, via the Hebrew Literacy Campaign and the Hebrew Reading Marathons. Indeed, to date, over 200,000 Jewish adults have learned to read the prayer book using his books Shalom Aleichem, Ayn Keloheynu, and While Standing on One Foot, which are still in use ten years after his death.

In the 1970s, I discovered this Yiddish booklet at the Jewish National and University Library in Jerusalem. I sent a photocopy to my father and asked him what it was. I was especially stricken by the date. It was published by YIVO in New York in January 1939, just seven months after my father arrived in the U.S. and just seven months before the outbreak of World War II and the Holocaust, which resulted in the destruction of YIVO, the Jews of Vilna, and most of the Jews in Europe. He recalled writing the pamphlet. He had had a premonition of what was to follow and he wrote it as a monument to both the Jews of Vilna and to YIVO.

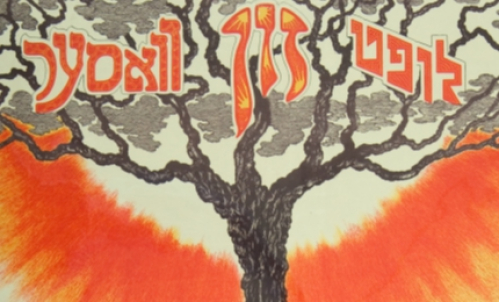

It is very hard to read this booklet without a feeling of great sadness. YIVO in Vilna was the equivalent of a Yiddish university and language academy all rolled into one. Just as YIVO began to standardize the spelling of Yiddish and to engage in extensive research projects, just as Yiddish was becoming a language of high culture, YIVO in Vilna was destroyed--along with a very high percentage of the native Yiddish speakers in the world.

I have translated this booklet into English as a memorial to my father Rabbi Noah Golinkin, z"l, on his tenth yahrzeit and in honor of his 100th birthday which will fall during Chanukah 5774. It is also dedicated to the memory of my uncle Eliyhau Yosef Golinkin, z"l, who served as a teacher and principal in Ivye (Iwie) not far from Vilna, who died in Alma Ata, Kazakhstan in May of 1944 to where he had fled from the Nazis, and to the memory of the six million Jews, most of whom spoke Yiddish and many of whom had great love and respect for YIVO. I have added brief notes in order to explain some Yiddish and Hebrew terms and to supply short biographies of the people mentioned. I wrote the original page numbers in brackets so that readers can compare the translation to the original. I hope that this booklet will help teach Jews about Yiddish and Eastern European Jewry and spur them to learn more.

Rabbi Prof. David Golinkin

25 Adar 5773

The Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies

Jerusalem

Rabbi David Golinkin was born and raised in Arlington, Virginia. He made aliyah in 1972, earning a B.A. in Jewish History and two teaching certificates from The Hebrew University in Jerusalem. He received an M.A. in Rabbinics and a Ph.D. in Talmud from the Jewish Theological Seminary of America where he was also ordained as Rabbi.

Professor Golinkin is President and Professor of Jewish Law at the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies in Jerusalem. For twenty years he served as Chair of the Va’ad Halakhah (Law Committee) of the Rabbinical Assembly which writes responsa and gives halakhic guidance to the Masorti (Conservative) Movement in Israel. He is the founder and Director of the Institute of Applied Halakhah at The Schechter Institute whose goal is to publish a library of halakhic literature for the Conservative and Masorti Movements. He is also the Director of the Center for Women in Jewish Law at the Schechter Institute whose goal is to publish responsa and books by and about women in Jewish law.

Rabbi Golinkin is the author or editor of forty-five books, including Halakhah for Our Time, An Index of Conservative Responsa and Halakhic Studies 1917-1990, Responsa of the Va’ad Halakhah, Be’er Tuvia, The Responsa of Prof. Louis Ginzberg, Rediscovering the Art of Jewish Prayer, Proceedings of the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards 1927-1970, Ginzey Rosh Hashanah, Responsa in a Moment (2 volumes), The Jewish Law Watch, The Status of Women in Jewish Law: Responsa (Hebrew and English editions), The Shoah Scroll, Insight Israel: The View from Schechter (2 volumes), To Learn and to Teach, The High Holy Days by Rabbi Hayyim Kieval, Responsa and Halakhic Studies by Rabbi Isaac Klein, Za’akat Dalot: Halakhic Solutions for the Agunot of our Time, Taking the Plunge by Rabbi Miriam Berkowitz, Essays in Jewish Studies in Honor of Prof. Shamma Friedman, Jewish Education for What? and other Essays by Walter Ackerman, The Schechter Haggadah, the Hebrew edition of Legends of the Jews by Louis Ginzberg, Ask the Rabbi, and The Student Struggle Against the Holocaust. He authored a column entitled “Responsa” which appeared in Moment magazine from 1990-1996. From 2000-2006 he authored a monthly email column entitled “Insight Israel” at www.schechter.edu. His current email column on that website is entitled “Responsa in a Moment”. He has published over 200 articles, responsa, and sermons

[Download a PDF of the original Yiddish.]

The Center of Yiddish Scholarship

By Dr. N[oah] Golinkin

Published by the American Division

of the Yidishn visnshaftlekhn institut

(Amopteyl)

New York, January, 1939

[PAGE 2]

YIVO – A World Center

On mountains and valleys lies, spread out, the beautiful city, the darling city of today's Poland: Vilna. It is as magic a word for lovers of nature as it is for lovers of culture. Three cultures intersect here: Polish, Lithuanian, and Jewish. Each invested its share here; each fastened its hopes to it. But no one came up with a more beautiful pet name, breathing more love and respect, than the Jewish name: Yerushalayim d'Lita, The Jerusalem of Lithuania.[2]

The Jerusalem of Lithuania is the symbol of Jewish learning and piety, of the Vilna Gaon, the Vilna synagogue, and the Vilna Shas.[3] The Jerusalem of Lithuania is the symbol of the Haskalah, of Rashi Fuenn, the Strashuns, Kalman Shulman, and Ze'ev Yabetz.[4] The Jerusalem of Lithuania is the cradle of Mizrachi, on the one hand, and of the Bund on the other.[5] Vilna is the city of yeshivas , of Yiddish and Hebrew folkshuls [elementary schools] and gymnasia [high schools]. Vilna is the place where the famous Vilna Yiddish is spoken.

Therefore, it is no surprise that Vilna recently merited going up one more notch: to [page 3] become the center of Yiddish scholarship for the entire world, to become the seat of the Yidishn visnshaftlekhn institut [Yiddish Scientific Institute] (YIVO). The city with an exalted and rooted tradition of Jewish spiritual creativity had the ambition to become the center from which Jewish, modern scholarship would radiate over all the lands of Jewish dispersion.

From the quietest street of the dreamy city stretch mysterious threads to New York and Chicago, to Melbourne in Australia and Johannesburg in South Africa, to Paris and London, Belgium, Uruguay and Peru, and to wherever there is a Jewish community. As is the destiny of our people, so is the destiny of our scholarship. Both are international, neither recognize borders of lands and continents. YIVO is the first attempt to embrace the entire planet.

There were and are many Jewish scholarly institutes of the most diverse types in various lands. Until YIVO, however, there was no such thing as THE Yiddish Scientific Institute, the only, central one for all Jews.

[page 4] It was a sign of the times, of the dreams of assimilation, when there arose in Germany the various Gesellschaften zur Forderung der Wissenschaft des Judentums [Societies for the Advancement of Jewish Scholarship], and the English and American [Jewish] historical societies, etc.[6]

Their activities were limited to one land, their interests were aimed primarily at the past and not toward the present and future; thus, their particular interest in history. Their goal was the achievement of emancipation and complete equal rights in their countries of residence. They therefore also aspired to cut themselves off as much as possible from world Jewry, to isolate themselves from other Jews, in order to make it easier to assimilate with their hosts.

With the emergence of Jewish national consciousness, one realized all the more the baseless nature of the assimilatory streams and of the obstacles this created for researching Jewish phenomena. An important gap arose in our spiritual life, and that gap was filled by the Yiddish Scientific Institute, which arose just thirteen years ago.

[page 5] Thirteen years is a very short time, but in that short time the Institute has been distinguished by very great successes. The Institute is progressive, but at the same time, it has a great love for tradition. A Jewish boy becomes a bar mitzvah at age thirteen; he devotes himself to a reckoning of his life until that point and undertakes to fulfill important duties in the future. Not long ago, the Institute also celebrated its bar mitzvah in an impressive and serious fashion. Lectures were given, brief work results were published; a reckoning of the past took place, and paths for the future were outlined.

YIVO is interested in all phenomena of Jewish life and not only in the history of the past. It registers all phenomena, day in, day out, and collects all Jewish newspapers from around the world in all seventy languages.[7]

It collects all new and old books in Yiddish or in foreign languages about Jews. It collects old pinkasim,[8] new brochures, and the most diverse printed materials of any worth.

It collects manuscripts, photographs [PAGE 6] and autographs of famous Yiddish and Hebrew writers and communal leaders. It collects old folksongs, old folktales, puremshpiln [plays], and children's plays. It collects Yiddish jokes and proverbs. It collects and preserves Jewish antiquities: mizrakhn, shir hamaylesn, megiles, and snuff boxes.[9]

Everything which is able to and which has a purpose to reflect Jewish life, is valued and collected in the archives and museums of the institute.

YIVO has three archives and three museums. The press archive is the richest in the Jewish world. It already has 10,000 volumes of Jewish newspapers. The theatre museum is the only one in the world. It holds letters, pictures, manuscripts, and posters of actors and playwrights. The folklore committee has a hundred thousand Jewish folklore items.

The bibliographical center possesses a list of 220,000 books and periodicals. The library has over 40,000 books. It contains rare books and manuscripts.

In gathering the materials, hundreds of collectors and correspondents helped; they dedicated themselves to scholarly assistance at the call of [page 7] YIVO and according to its instructions.

In order to conduct the diversified research effectively and systematically, the Institute is divided into four main sections: 1) philological; 2) economical-statistical; 3) psychological-pedagogical; 4) historical. From this, it is apparent what an important role it will play in research of “living life” in the here and now. The problems around which the research in the first three sections revolves are not only theoretical but also practical.

Here one sees problems of Yiddish style and orthography side-by-side with research of classics of old literature, and of monographs about writers and works. Here one gets a social picture of Jewish life in the Eastern European lands in all its hues. Here there are also modern educational problems, the psychology of children and parents, and the ways and trends of today's Jewish youth. In the latter domain, a contest was conducted that yielded 312 autobiographies by [page 8] Jewish youth from 8 countries. These autobiographies comprise approximately 17,000 pages. Diaries were also entered into the contest; they comprise approximately 10,000 pages. This material gives an excellent picture of the economic, psychological, and social problems of Jewish youth.

In order to give expression to the work of YIVO in its diverse sections, four journals are published: 1) YIVO bleter [YIVO Pages]; 2) Yidishe Ekonomik [Jewish Economics]; 3) Yidish far ale [Yiddish for Everyone]; 4) and a bulletin, Yedies [News].[10]

Moreover, YIVO publishes individual books of great scholarly significance, written by famous authorities. It also publishes anthologies such as Historishe shriftn [Historical Writings], Philologishe shriftn [Philological Writings], and Ekonomishe shriftn [Economic Writings], as well as anthologies about theater, bibliography, psychology and pedagogy, and other fields.

These writings contain a tremendous amount of valuable and very interesting work. They already comprise over 25,000 pages, published with the complete scholarly apparatus: modern, good paper and printing, with illustrations, tables, and photostats. All of the work is conducted in Yiddish, in the language of the majority of the Jewish people, but this does not prevent the Institute from [page 9] standing above all language conflicts and party politics. The Institute is apolitical and it enjoys the respect and cooperation of all tendencies; Hebraists and Yiddishists, Zionists and Bundists, religious and secular -- all regard the fruitful work of the Institute with love and warmth.

YIVO has won over not only Jews but Christians, as well, among them such personalities as Lord Marley from England,[11] Prof. D. Simpson from Oxford, and many Polish authors. YIVO has become the Mecca of Vilna. When a Jew with only the barest enthusiasm for cultural affairs arrives in Vilna, he is drawn to drop in for a while at a scholarly workshop, at YIVO. Each visitor leaves with a powerful impression of the work which goes on there. Nahum Sokolow of blessed memory went away from there with a blessing on his lips, and Berl Locker promised that he will come again; he did not want to leave.[12]

Wherein lies the charm? It lies perhaps in the boldness and magnificence of the challenge. It lies perhaps in the systematic nature and organization of the multifaceted work. [page 10] Perhaps they are captivated by the innumerable drawers, where lie written out on cards hundreds of remedies against headaches, toothaches, or stomachaches. The curses and the blessings of Vilna market Jews, the jokes and the aphorisms of the Volhynian Jews.[13]

Perhaps they are captivated by the Esther-Rachel Kaminska Theater Museum, the old costumes of the actors.[14] Perhaps they were impressed by a chart on the wall containing a map of Poland which marks with special colors the towns where the people say di oyg [the eye] or dos oyg [the eye]. This is a very important matter. One must, once and for all, decide, should one say di oyg or dos oyg? And as the majority will agree, so will it remain.[15]

The visitor can also catch enthusiasm from the iron and cement cellar where, in a massive vault, a treasure of rare letters from our classical authors and from important historical personalities is locked up. A European visitor will certainly be surprised to see, among the tens of thousands of books and newspapers from all corners of the world, [page 11] the enormous, fat volumes of the latest volume of the New York Forverts.[16] As he goes up the stairs, he encounters a map of the world: he notices at once where our 17 million Jews live,[17] where one speaks Yiddish, where there are branches of the "Friends of YIVO" Organization. If he ascends higher, he can drop in on an interesting scholarly lecture which is being heard by a few hundred Vilna intellectuals.

He can, however, also get lost on the side and drop into the study rooms, where young men and women are sitting engrossed over books and taking notes. Who are they? These are still not well-known scholars, but they might become such scholars in the near future. Three years ago, after the death of Dr. Zemach Shabad (one of the founders of YIVO),[18] it was decided to create a new Institute in his name. It was given the name "Aspirantur" [Research Fellows]. Jewish young people, who completed a university and were interested in Yiddish [or Jewish] scholarship, would be able to test their abilities, and, under trained guidance, [page 12] conduct research work which would later enable them to become independent scholars. From among hundreds of candidates are carefully selected twenty of the most talented, who devote themselves to research work.

The results are splendid. Every year, important areas of research are dealt with and the young researchers become enriched by a lot of practical experience. Their works are also published afterwards.[19]

Another nice thing: It has already become a tradition at YIVO to arrange exhibitions of the works of writers and artists. The exhibitions of Mendele and Peretz were very impressive. Here you saw the oldest manuscripts and editions of their works, translations into different languages, reviews, posters about their lectures, photographs of them themselves, of their families, of all the places where they lived. All were arranged according to a precise system and accompanied by charts and captions, which, on their own, furnished complete, lively biographies of the writers. Here you saw Peretz's famous cape, his cane, his hat, and the entire [page 13] room where Peretz lived and created.[20]

Here one discovered that our classical authors have been translated not only into Russian, Polish, German, French and English, but also into Hungarian, Romanian, Spanish, and even Arabic. Here you saw autographic postcards written from grandfather to grandson and vice versa (Addressed: Sholem Aleichem, Aleichem Sholem!)[21] and the complete, extensive correspondence of our writers. Esther-Rachel Kaminska and David Herman also had beautiful exhibitions in honor of their yahrzeits.[22]

It is, however, a mistake to think that all the work is concentrated within the four walls of the Vilna Institute. In America, we have an Amopteyl (American Division) of YIVO. In Argentina, we have an Argopteyl. The "Economic Section" is mainly active in Warsaw, where Jacob Lestschinsky resides. The secretary of the history section, Elias Tcherikower, is in Paris. The secretary of the psychology section, Leibush Lehrer, is in New York. Vilna is, for the most part, the center of the philological section under the direction [page 14] of Dr. [Max] Weinreich.[23]

In thirteen countries, in all parts of the world, there are "Friends of YIVO" organizations. They support the institute with money, but they are also helpful in collecting the necessary scholarly materials. In addition, they are frequently the headquarters of Yiddish cultural life in their respective locations.

Recently, Warsaw also created a special "Historical Commission for Poland,” in order to collect materials necessary for serving as a basis for monographs about various Polish cities. A successful campaign was carried out to find old, historic pinkasim.[24] There is a historical circle that arranges lectures and publishes periodic "Historical Papers." There are also similar circles of economists, pedagogues, and psychologists who do important work. Lodz is active in the historical domain and publishes "Lodz Scholarly Writings." Paris is the center for historians and is now collecting material for the history of Yiddish theatre in France.

Y. N. Steinberg and M. Gaster head the work in London and [page 15] are getting prepared to publish a historical anthology: "Jews in England.”[25]

In New York, one finds one of the most active YIVO researchers, the historian Dr. Jacob Shatzky, who not long ago published a large, fundamental work about Gzerot Takh-Tat ( [the Chmielnicki massacres].[26] The New York YIVO published a Year Book in 1938; now they are on the verge of publishing a second Year Book for 1939. Recently, a historians' circle has been active at the Amopteyl; it arranges historical lectures. In addition, YIVO in New York organized a forum where renowned authorities give lectures about history, literature, art, philosophy and philology. The Argentinean Division is also getting prepared to publish an anthology.

In a word, fruitful, lively work is going on in all areas of Yiddish scholarship, at a tempo which hasn’t been seen until now. Yiddish, which was until recently only the language of the common folk, or at the most of literature, has reached the level of a high cultural language in which serious works are being written.

When we recall that just [page 16] thirty years ago it was an exalted dream to publish cheap, popular booklets about thunder, lightning, and the origin of rain for the people, and now YIVO publishes works by Freud and Spencer in Yiddish translations, one becomes proud and happy.[27]

On the one hand, the common people have become mature enough to read such works; on the other hand, the intellectuals have become folksy, they are no longer ashamed to read scholarship in Yiddish. Above all: Yiddish has come out of the shadows and become a language of scholarship.

YIVO has certainly had a great part in this, and its founders – Zalmen Reisen, Dr. Max Weinreich and Zelig Kalmanovitch – deserve a true yasher koyekh [congratulations].[28]

As Opatoshu said: “From Sura-Pumbedita to YIVO is our path.”[29]

[1] For biographies of Rabbi Noah Golinkin, see David Golinkin, Insight Israel: The View From Schechter, Jerusalem, 2003, 157-167 (www.schechter.edu/insightIsrael.aspx?ID=76); Rafael Medoff, Encyclopaedia Judaica, second edition, 2007, Vol. 7, 740-741; Rafael Medoff and David Golinkin, The Student Struggle Against the Holocaust, Jerusalem, 2010, especially 121-127.

[2] According to Lucy Dawidowicz, From That Place and Time: A Memoir 1938-1947, New York and London, 1989, xiii, Napoleon is said to have coined this phrase in 1812!

[3] The Vilna Shas or Talmud was published by the Widow and Brothers Romm in 1880-1886 and became the gold standard. Most subsequent Talmud editions were simply offsets of that edition.

[4] The Haskalah or Enlightenment was a Jewish spiritual and social movement in eighteeenth-century Germany and nineteenth-century Eastern Europe. Its goals were the education of the masses, the integration of Jews with non-Jews, Jewish civil rights, and the renewal of secular Hebrew language and literature. Rashi or Rabbi Shemu’el Yosef Fuenn (1818-1890) was a prolific Hebrew writer of the Haskalah and an early member of Hoveve Tsiyon.

The Strashuns were Rabbi Shemu’el Strashun (1794-1872), who wrote extensive glosses on the Talmud published in the Vilna Shas (see note 3, above), and his son Rabbi Matityahu Strashun (1819-1885), a Talmudic scholar and author. In 1892, his library of 5,700 volumes became the Strashun Library, a public library for the Jews of Vilna, which was transferred to its own specially erected building in 1901. By the late 1930s, the Strashun Library contained over 35,000 books and 150 manuscripts. My father no doubt used that library. When the Nazis occupied Vilna in June 1941, they destroyed some of the books and transferred others to Frankfurt. After the Holocaust, Lucy Dawidowicz identified some of the Strashun books in the Offenbach Archival Depot run by the U.S military and they were shipped to YIVO in New York along with many YIVO books from Vilna which she identified – see her book (above, note 2), pp. 318-326. My thanks to my brother, Cantor Abe Golinkin, for this reference.

Kalman Shulmann (Vilna, 1819-1899) was a Hebrew author and member of the Haskalah and a historian who translated Josephus into Hebrew. Ze'ev Yabetz (1847-1924) was an Orthodox historian who published a twelve-volume history of the Jewish people in Hebrew.

[5] Mizrachi was the religious Zionist party founded by Rabbi Yitzhak Ya'akov Reines in 1902. My grandfather Rabbi Mordechai Ya'akov Golinkin (1884-1974) was a lifelong member. It later became the Mafdal/Bayit Yehudi party in Israel. The Bund, a shortened form of the Algemeyner Yidisher Arbayter-Bund fun Rusland, Lite un Polin (The General Jewish Workers Union of Russia, Lithuania and Poland), founded in Vilna in 1897, was socialist, anti-Zionist, and devoted to Yiddish and secular Jewish nationalism in Eastern Europe. It was very influential until the Holocaust.

[6] The Gesellschaft, which existed in Berlin from 1902 to 1938, sponsored lectures and grants to scholars and published the prestigious academic journal MGWJ and an important series of monographs by leading writers and thinkers. (Encyclopaedia Judaica, vol. 7, cols. 523-524). The Jewish Historical Society of England was founded in 1893 and the American Jewish Historical Society in 1892.

[7] Seventy languages is a Talmudic phrase (Megillah 13b) and should not be taken literally.

[8] Pinkasim were books which collected the customs and regulations of a specific town or region, frequently over a very long period of time. The most famous pinkas is Pinkas Va'ad Arba Aratzot, of the Four Lands (Great Poland, Lesser Poland, the Lvov Land and Volhynia), which was written between the mid-16th to mid-18th centuries.

[9] Mizrakhn are the signs or posters which hang on the eastern wall of a synagogue. Shir hamaylesn are amulets hung on the wall of a mother who just gave birth. They contain the sentence "Adam and Eve barring Lilith," the names of three angels whom Lilith dreads, the names of Lilith, and Shir hamayles (Psalm 121). See Hayyim Schauss, The Lifetime of a Jew, New York, 1950, 55. Megiles are megillot or scrolls of Esther written by hand on parchment.

[10] YIVO bleter appeared in Vilna and then in New York from 1931-1997. Yidishe Ekonomik was published in Warsaw and Vilna 1937-1939. Yidish far ale appeared in Vilna 1938-1939, and Yedies fun YIVO has been published in Warsaw, then in Vilna, and later in New York from 1925 to the present day.

[11] Lord Marley's given name was Dudley Leigh Aman (1884-1952). He was elected to the British Parliament in 1930. In 1933, he became an advocate for resettling oppressed German and Polish Jews in the Jewish autonomous region of Birobidzhan in the Soviet Union. See Nicole Taylor, Jewish Quarterly 198 (Summer 2005).

[12] Nahum Sokolow (1859-1936) was a Hebrew writer and president of the World Zionist Organization. Berl Locker (1887-1972) was a Labor Zionist Leader.

[13] Volhynia is a region in northwest Ukraine.

[14] Esther-Rachel Kaminska (1870-1925) was a famous actress in the Yiddish theatre company run by her husband Abraham Isaac Kaminski.

[15] In Yiddish, the definite article is der (masculine) or di (feminine) or dos (neutral) -- see Uriel Weinreich, College Yiddish, fifth revised edition, New York, 1971, p. 31. In this case, there was a disagreement as to whether oyg is feminine or neutral. Regarding the dialects of Yiddish and deciding according to the usage of the majority, see ibid., 43-44.

[16] The Forverts, which began to appear in 1897, is the longest-running Yiddish newspaper in the world. The English language Forward began to appear as an independent weekly in 1990.

[17] According to The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Vol. 10 (1943), there were 16,723,800 Jews in the world in 1939, 23.

[18] Dr. Zemach Shabad, or Szabad (1864-1935) was a physician and communal leader in Vilna.

[19] Lucy Davidowicz, who later became a well-known Holocaust historian, published an entire book about her experiences as an aspirantur at YIVO in Vilna in 1938-1939. See above, note 2. My Aunt Rochel/Rachel Golinkin (later: Sherman), the sister of Noah Golinkin who wrote this pamphlet, was an aspirantur at YIVO that very same year – see Dawidowicz, 68-69, 94, 189, 216-217.

[20] Mendele Moykher Seforim (1834-1917) and Y.L Peretz (1852-1915) are considered, together with Sholem Aleichem (1859-1916), the three founding fathers of modern Yiddish literature.

[21] This seems to be a hint of a correspondence between Sholem Aleichem and his grandson.

[22] David Herman (1876-1937) was a well-known producer of Yiddish plays in Warsaw and the director of the Vilna Troupe, for which he staged the first production of The Dybbuk in 1920.

[23] Jacob Lestschinsky (1876-1966), was a pioneer in Jewish sociology, economics and demography. Elias Tcherikower (1881-1943) was a prolific writer on modern Jewish history. Leibush Lehrer (1887-1965) was a Yiddish writer and educator. Max Weinreich (1894-1969), one of the founders of YIVO in Vilna and one of its pillars in the U.S., was a prolific Yiddish linguist, historian and editor.

[24] See above, note 8.

[25] Isaac Nachman Steinberg (1888-1957) was a Russian revolutionary, jurist, writer and leader of the Territorialist movement, which advocated Jewish colonization in other countries besides Palestine. Rabbi Moses Gaster (1856-1939) was the Hacham of the English Sephardic community, a Zionist leader, and a very prolific scholar in at least seven fields in many different languages.

[26] Jacob Shatzky (1893-1956) was a very prolific Yiddish author in many fields and one of the founders of the U.S. section of YIVO.

[27] Possibly Herbert Spencer (1820-1903), an English philosopher, biologist, anthropologist, sociologist, and prominent classical liberal political theorist of the Victorian era.

[28] Zalmen Reisen (1887-1941) was a Yiddish philologist and literary historian. Regarding Max Weinreich, see above, note 23. Zelig Kalmanovitch (1881-1944) was a Yiddish writer, philologist, and translator.

[29] Joseph Opatoshu (1886-1954) was a Yiddish novelist and short-story writer who wrote for Der Tog for forty years. Sura and Pumbedita were the main Talmudic academies in Babylonia in the period of the Geonim (ca. 500-1000 C.E.).