Turning the Shtetl Upside Down: An Interview with Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern

On Wednesday, March 19, 2014, Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern, Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies at Northwestern University will give a talk at YIVO about his new book, The Golden Age Shtetl: a New History of Jewish Life in East Europe.

The shtetl was home to two-thirds of Eastern Europe's Jews in the 18th and 19th centuries, yet it has long been one of the most misunderstood chapters of the Jewish experience. Challenging popular misconceptions of the shtetl as an isolated, ramshackle Jewish village stricken by poverty and pogroms, Professor Petrovsky-Shtern argues that, in its heyday from the 1790s-1840s, the shtetl was a thriving Jewish community, as vibrant as any in Europe. His book presents the shtetl as a Polish private town belonging to a Catholic magnate, administratively run by the tsarist empire, yet economically driven by Jews. Jews turned the shtetl marketplace into a supermarket. They smuggled and drank vodka, seeing in both actions a moment of freedom. They built houses that served as urban stores and village barns and purchased Hebrew books they could not understand. In addition, they surrounded themselves with the symbols of the Holy Land and Jerusalem, although they were not actually planning to leave for Palestine.

The Golden Age Shtetl: a New History of Jewish Life in East Europe will be available for sale at the event. Books will be sold through McNally Jackson bookstore.

Attend the event.

Buy the book.

Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern is the Crown Family Professor of Jewish Studies at Northwestern University. He is the recipient of multiple grants and awards, including a Northwestern University Distinguished Teaching Award. He has been appointed a Fulbright Specialist on Eastern Europe, a Fellow at the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, and a Visiting Professor at the Free Ukrainian University in Munich, and has been awarded a doctor honoris causa degree by the National University Kyiv-Mohyla Academy in Ukraine. Petrovsky-Shtern has published five books on East European Jewish history and is currently co-authoring a documentary about the history of the Jews in the early modern world.

He is interviewed here by Leah Falk.

LF: In your book, The Golden Age Shtetl, you’re working against a common perception of the shtetl as an impoverished, isolated village, and arguing that there was actually a time when Jews did quite well under Russian rule.

YPS: Yes, I do work against the common understanding of the shtetl as the impoverished Jewish village in the middle of nowhere where nothing happens but pogroms. I’m saying that between the 1780s and the 1840s the shtetl had been a robust, economically vibrant and communally burgeoning town at the crossroads of major caravan and trade routes in East Central and Eastern Europe. We are missing this story, because usually we look at the late 19th early 20th century shtetl or at the pre-Holocaust shtetl, and very little remains of that particular golden age. I’m taking the shtetl in the age of its glory, late 18th to early 19th century, and I’m asking, what do we call the shtetl at that time? And I’m working outside the established historiographic framework; I’m saying, let’s take a look at what’s happening on the ground.

LF: Why do you think that that period has become lost to the public imagination?

YPS: Historians such as Hundert, Rosman and Teller did excellent work uncovering the realities of private Polish towns in the 18th century. But they didn’t work with the Russian or Ukrainian language, so they could not look at the same territories after the 1780s and ‘90s. On the other hand, Russian Jewish historians predominantly worked with Russian sources that were vertically oriented, that conveyed what was going on between the central government in St Petersburg and the abstract Jews. Very few, if any, looked at what was going on at that time in the shtetl proper. Not what St. Petersburg wants to do to it, not how it wants to reform the Jews in newly acquired borderlands of Russia, but rather how people feel, what people think, what do they dream about and what do they do in their immediate environment—Jews, Poles, Russians, Ukrainians.

Why is this important? I believe Russia lost its wonderful chance to create a vibrant, trade-based economy in its newly acquired western borderlands. Because for Russia, from the late 1830s onward, ideology became more important than economics. Of course, Russian authorities, Nicholas I, for example, did care about the country’s economy, but suppressing Poland and Polish presence in these territories was much more important than anything else.

LF: Let me backtrack a little. You mentioned earlier that your focus on the internal history of the shtetl is perhaps more thorough than that of your predecessors. What of that internal history might we be surprised by, those of us who have an idea of the shtetl that’s a little more “Fiddler on the Roof”? What exchanges or habits of life might surprise us?

YPS: Every chapter of the book covers a particular topic that goes against the received wisdom about the shtetl. Let’s take a look at the shtetl’s marketplace. In “Fiddler on the Roof,” you do see the marketplace, where several women are trading in pottery, groceries, milk, cheese, things like that. Very low-key trade. When I look through the registers of goods available at the marketplace, at practically any marketplace in two to three hundred towns in central Ukraine, I don’t see the market, I see the supermarket. And what is available there is breathtaking. You would find there commodities for any taste and demand: for the Polish magnates, for the rank-and-file Poles, for the Polish urban-dwellers, Russians or Ukrainians, for peasants, for Cossacks, for Jews, for wealthy merchants, for poor people, for women, children, from people looking for luxurious commodities to people looking for herring—amazing diversity.

Of course, since economy is the core of the shtetl, it shapes everything around it. It shapes how Jews live, get married, find jobs, interact with one another; it also shapes the architecture of the shtetl and, of course, Jewish/Gentile relations.

Let me pause here. People know that the word pogrom, like the word Sputnik, is a Russian gift to western civilization. Let’s forget about Sputnik and talk about pogroms. The last pogroms in central Ukraine happened around the 1760s during the Haidamak rebellion, which was an anti-Polish popular uprising. When do we have the next period of mass violence against Jews? The 1880s. Between the 1760s and 1880s, a period of 120 years, we do not have any kind of pogroms or mass violence on these territories. Where is the anti-Jewish violence?

I’m looking at a plethora of court cases, complaints and appeals to the governor and local police reports: Jews suing Polish magnates in Russian courts and winning. Jews beating Russian policemen. Jews mocking Christianity in public.

Violence in the golden age shtetl does not belong to Christians, Ukrainians; it does not have ethnicity. Violence—verbal, rhetorical, physical—is a typical and normative modus vivendi of the shtetl. Anybody who wants to partake of it, partakes of it. Ukrainians know Yiddish curses, Jews know Ukrainian curses. We are dealing with equal opportunity violence.

LF: What brought back pogroms after this long period of “equal opportunity violence”? Can you attribute it to Jews’ decreased economic power?

YPS: First, the decline of Jewish economic activity, Jews no longer play a particularly formidable role in the shtetl economy. The second issue is more complex: it is about the Jews and the Russian army. What is going on in the shtetl in terms of army accommodation? The Russian army doesn’t live in the barracks. The army’s billeted in the houses of the shtetlakh. For half a year, from October till April, the Russian army is quartered in towns. The soldiers stay with peasants, the officers and generals stay with Jews. This happens in the 1790s, 1800s through 1870s. But in the 1870s, as the result of the military reform in Russia, barracks are built and troops are moved into the barracks. No troops are billeted in towns unless it is wartime.

Let us imagine that in the 1820s, you and I are those wild, stereotypical and therefore never-existing Ukrainian peasants who just want to kill the Jews. Let’s say we go to the shtetl and we want to beat the crap out of that tavern keeper to whom we owe money and whom we don’t want to pay. We step in with our bats. Who do we see? We see officers. So you want to arrange a pogrom? We cannot do that. But in the 1880s, that situation radically changes. Not only because of the decline of the Jews’ economic power, but also because of the decline of their housing, and because the army’s not there. With the army not in town, you have one policeman for ten, fifteen thousand people. What can he do? The regular army, anywhere in Europe, doesn’t have experience suppressing urban riots. Look at what is going on in Ukraine right now—they still don’t know how to do that.

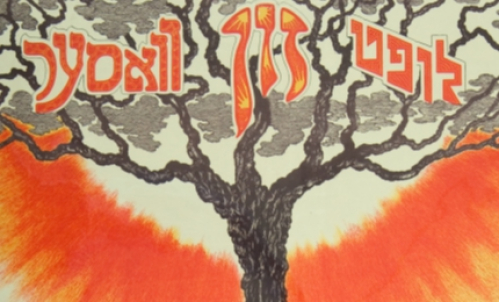

LF: I wanted to ask you about the cover image of your book. You’re an artist and that’s your painting on the cover. What, in your view, does that image transmit about the shtetl? Do you think it sends an affirmation of ideas we might already have? Or does it challenge those ideas?

YPS: It shows that the shtetl is very much a self-contained entity. It’s a “yin-yang.” You have two opposites that are united in one. You have a woman with a jar of milk, or honey, anything that has something to do with physicality—and you have a topsy-turvy man with a book, with his spirituality. These two opposites cannot exist without one another. You can look at it both ways, turning the picture upside down. Also the word “sefer” [book] is written upside down. Since everything is topsy-turvy, and mutually complementary, it does convey an important principle—after all I’m turning upside down received concepts with which we look at the shtetl.

LF: I’ll close with one forward-looking question: if the descendants of the Jews you’re writing about could internalize the portrait you paint of this golden age, how do you think that would change our notions of our history—even for those of us who are several generations removed from that heritage?

YPS: It would add a sense of pride. I have given a couple of lectures on the book already: I just gave one at the American Association of Friends of Hebrew University. After my lecture, a couple of women came up to me and said: “You know what? My grandmother was an innkeeper, she always traded in contraband, and she knew that if my grandfather wanted to have a sense of freedom he would open a bottle of brandy and have a nice good shlok un nokh a shlok. So what I’m creating in the book, I hope, is momentarily recognizable. It’s Eastern European, Slavic, and very much embedded into the Jewish memory. It’s like the knob which sits there but you don’t touch it—there’s no sense that it’s a functional knob. It is a functional knob, which you do not see, but once you touch it, it revives the memories.

Interview edited for length and clarity.

Leah Falk is YIVO’s Programs Coordinator.