Yiddish with Footnotes: Vilna 1913

by MAURICE WOLFTHAL

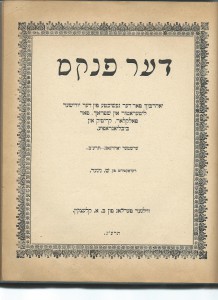

One hundred years ago there appeared a scholarly journal – complete with footnotes, bibliographies, and a page of errata at the end - that was revolutionary in two ways. Der pinkes: Yohrbukh far der geshikhte fun der yidisher literatur un shprakh, far folklor, kritik, un bibliografye (Annals: Yearbook for the History of Yiddish Literature and Language, Folklore, Criticism, and Bibliography), volume I, was a weighty academic tome that was written in Yiddish. And its object of study was Yiddish language and culture.

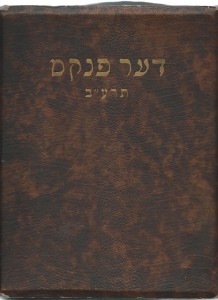

Published in 1913 in Vilna, then part of the Russian Empire, Der pinkes was an impressive volume, large in format, hardbound, with gilt lettering on the front cover and the impress of the publisher, Vilner ferlag B. A. Kletskin, on the back.

There had certainly been Yiddish scholarship before, but nothing like this. At the time, Yiddish was the vernacular for an estimated eleven million Jews. During its thousand-year history it had been the vehicle for translations and adaptations of the Torah; religious commentaries; prayers; books of customs; chivalric tales; fables; short stories; poems; novels; philosophical and satirical essays; and political pamphlets. John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty appeared in Yiddish translation, as did Anatole France’s Le Crime de Sylvestre Bonnard, Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts, and dozens of works by Russian and German authors. Yiddish newspapers and magazines had flourished at least since the seventeenth century. Songs and operas were composed in Yiddish. Plays were written and performed in Yiddish theaters from Moscow to New York.

The Yiddish language, whose status was still being hotly debated, was itself a major focus of Der pinkes. Impetus for such a volume undoubtedly gained momentum from the Czernowitz conference five years earlier, which had proclaimed Yiddish to be “a national language of the Jewish people,” worthy of scholarly study. Yiddishists of various political persuasions organized Yiddish-language kindergartens, schools, and high schools. Some, like members of the Bund - the General Jewish Workers’ Union in Lithuania, Poland, and Russia - believed that Jews should remain in Europe. Others saw no hope for the Jews in antisemitic Europe, and sought a territorial homeland of their own, most of them with Palestine in mind. But Yiddish was their common heritage.

The overwhelming majority of Yiddish speakers also spoke the dominant language around them, and among the more educated Jews there was a tendency to embrace the local language as a means towards social acceptance, access to the professions, and civil rights. Finally, there were Jews who wished to renew Hebrew as a vernacular, both out of historic pride and as preparation for emigration to Palestine. But these language constituencies were not rigid, and many intellectuals went through various phases on the language issue, as they did on the political questions facing Jews. This was true of many contributors to Der pinkes, including its editor, Shmuel Niger, who had written articles on politics and culture in Hebrew and Russian before turning to Yiddish.

To be sure, there had been studies of Yiddish by non-Jews, mostly German scholars. But in his essay in Der pinkes on “Di oyfgabn fun der der yidisher filologye” (The Tasks of Yiddish Philology), Ber Borokhov, founder of the Zionist Socialist Workers’ Union in Ukraine, stressed the importance of Jewish scholarship on Yiddish to reclaiming Jewish patrimony. Indeed other essays dealt with linguistics and medieval Yiddish; the system of Yiddish orthography (the standardization of spelling was one of Niger’s objectives); the language of medieval Jews living along the Black Sea; Yiddish phonetics; and the influence of the Hebrew sound system. There was a book review of Alfred Landau and Bernhard Wachstein’s Jüdische Privatbriefe aus dem Jahre 1619 (Private Yiddish Letters From 1619). And the final 66 pages of the volume were devoted to Borokhov’s exhaustive bibliography, the “Library of the Yiddish Philologist: Four Hundred Years of Language Research,” with 499 entries.

Niger contributed a historical inquiry, 27 pages long, into “Yiddish Literature and the Woman Reader.” The linguist Nokhem Shtif scathingly reviewed the Geshikhte fun der yidisher literatur (History of Yiddish Literature) of Dr. Meyer Pines, who had originally written it in French as his dissertation at the Sorbonne, L’Histoire de la littérature judéo-allemande. One memoir in Der pinkes concerned Mendele - short for Mendele Moykher-Sforim, pen name of Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh - the prolific author in both Yiddish and Hebrew. Another dealt with the literary career of Avrom Reyzen, the poet, short-story writer, and socialist activist.

The thriving Yiddish theater was covered with articles on Shloyme Ettinger, the early nineteenth-century Warsaw dramatist and on Avrom Goldfadn, the impresario who had written poems in Hebrew and Yiddish and whose Yiddish plays and operettas were staged throughout Europe and the United States. Der pinkes also featured a compendium of “The Repertoire of the Jewish Theater in America Until the 1912 Season,” and another of “The Repertoire of the Jewish Theater in Russia Until 1912.”

Journalism, too, was a focus of inquiry. There was piece commemorating the tenth anniversary of the first Yiddish daily newspaper in Russia, Der fraynt (The Friend), and another on the twentieth anniversary of the monthly socialist journal in New York, Tsukunft (The Future). There was a massive, annotated compilation of all the Yiddish newspapers and magazines in the world, including Argentina and South Africa. Equally impressive was a bibliography of all the Yiddish books that had been published in Russia in 1912. Moyshe Shalit contributed a statistical analysis of the Yiddish book market in 1912.

In the realm of folklore, there were two collections of Yiddish folk-songs as well as a review of Noah Prylucki’s 1911 Yidishe folkslider (Yiddish Folk-Songs). A scholarly interest in Jewish ethnography had motivated S. An-ski - pen name of Shloyme Zaynvl Rapoport - to found the Jewish Historical-Ethnographic Society in St. Petersburg in 1908 and to organize several expeditions on folklore in the Jewish Pale of Settlement in 1912-1914. That enthusiasm for anthropological research was reflected in Der pinkes in its review of Prylucki’s Zamelbikher far yidishen folklor, filologye un kulturgeshikhte (Anthology of Yiddish Folklore, Philology, and Cultural History).

There was to be no volume two of Der pinkes (though it was reprinted in 1922/1923), but it set a high standard for scholars throughout the Yiddish world. Later journals followed in its footsteps, among them Filologishe shriftn (Philological Writings), Di yidishe shprakh (The Yiddish Language), and YIVO bleter (YIVO Pages). In 1924 Nokhem Shtif circulated a short essay among his friends, arguing that Yiddish-speaking European Jews needed a university-level institution in their own language devoted to their own culture. The following year YIVO, the Yidisher visnshaftlekher institut (Institute for Jewish Research), was founded in Berlin. It soon moved to Vilna, where Der pinkes had been published, and its scholars pursued all the areas of research that Der pinkes had delved into. From 1941 to 1944 Hitler’s army looted and trashed the YIVO and murdered most of its researchers and staff. The Soviets sealed its fate.

But the single issue of Der pinkes stands as a shining reflection of the vibrant intellectual culture that once thrived in "Yiddishland," the tongue-in-cheek construct of a culture denied a territorial homeland of its own.

Maurice Wolfthal was a public school teacher for forty years. He is the author of an English translation of Yitzhak Erlichson's Yiddish memoir, My Four Years in Soviet Russia. He first encountered Der pinkes when he found a copy of the book on a trash heap outside the former headquarters of the Arbeter ring (Workmen’s Circle) on Hillman Avenue in the Bronx about twenty years ago.